What does "hyper-indie" success look like in 2025?

How to make sense of the fragmented gaming and information landscape

My guest for this issue of Multiplier is Tommy McKay, the creative lead at DYSTOPIAN. The Brisbane-based developer released GNOMES on Steam earlier this year.

Fergus: Video games have always been a hit-based business but as the market has grown bigger its become easier and easier to sight of what success actually looks like and how developers can set themselves up for it.

When the retail chains like EB Games were at the height of their power, you could look at sales charts. With digital distribution now the norm and audiences fragmented across countless platforms, it's become much harder to tell what is and isn't selling. Sure, you can point at Steam concurrents but you can't go too far without running up against the realistic limitations of the story that data can tell.

For many of those playing games, the stories we tell about the industry are often treated as a proxy for our perception about what is and isn't selling. Most people don't know enough about how much any given game might have cost to make, let alone market. Sometimes, it feels like the closest thing most people have to reliable sales data is a graphic on a social showing a slate of positive reviews or other accolades.

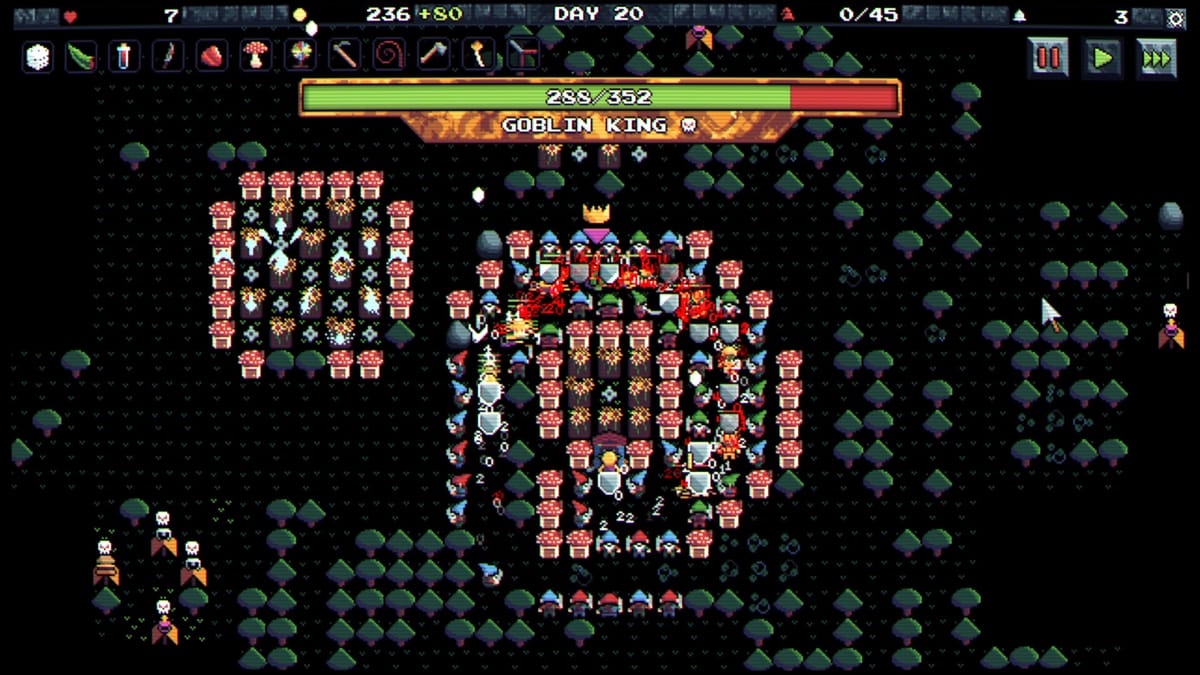

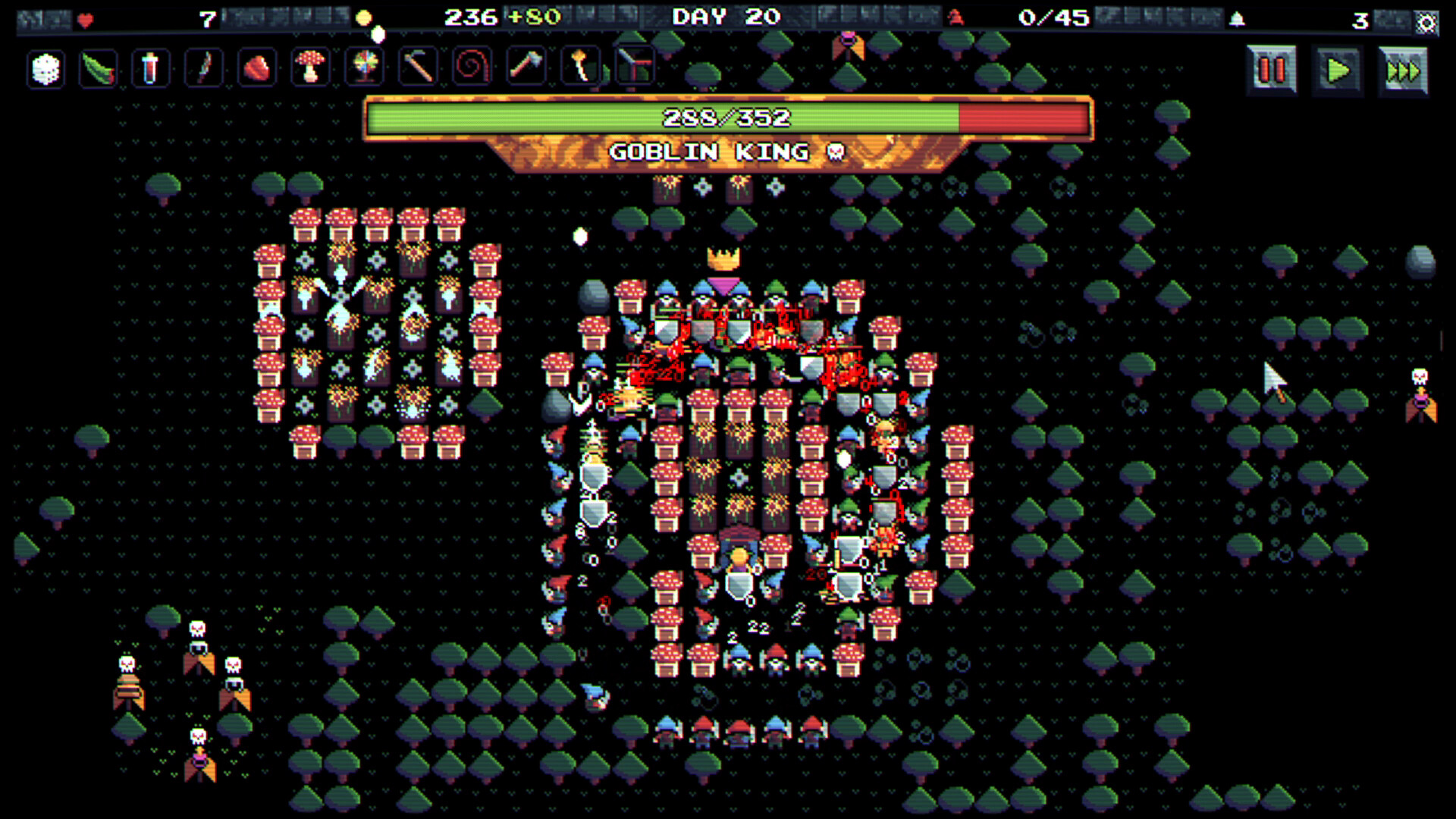

These days, the gaming landscape is broad enough and the media landscape stretched increasingly thin such that it's entirely possible for sleeper hits like Gnomes to find success despite their relative obscurity. If an Australian game sells over 25,000 copies in its first month and nobody reports on it, how can anyone learn from that success?

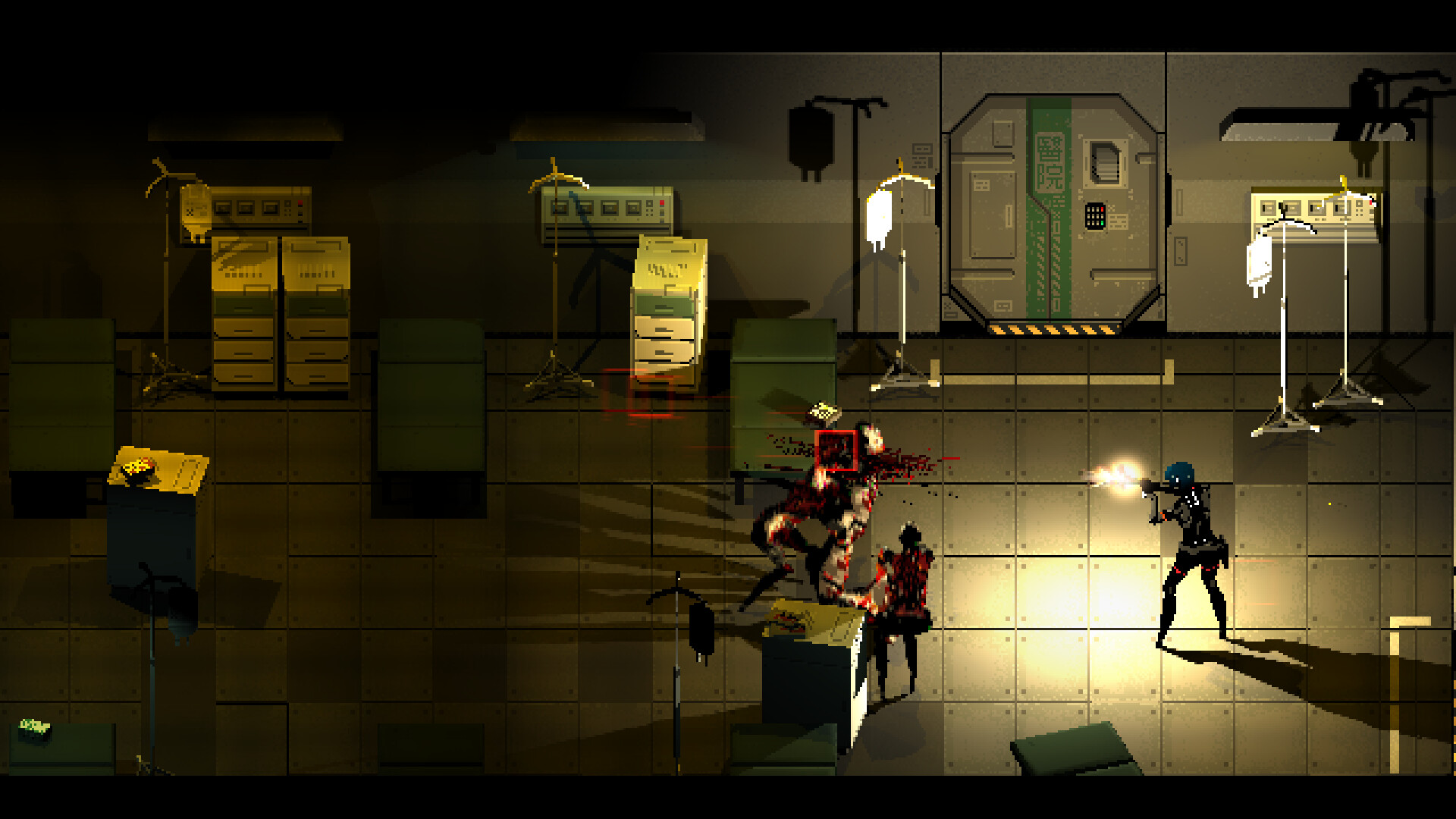

Tommy: I feel like the fragmentation caused by all this digital disruption has also led to a re-consolidation of what games are generally accepted across different platforms. Games that would have been at home on a free website like Newgrounds a few years ago are now able to top the Steam charts priced at $15-20, and they can do it without a budget, publisher or any major press. All it takes is a compelling demo and the right content creators to cover it and you're well on your way to a game that earns a comfortable living for a small team or solo [developer].

It's increasingly clear to me that the games press has been usurped by the YouTubers and Twitch creators. Their primary objective is to get eyeballs on their channel, and the best way to do that is to be the channel that discovers the next sleeper hit. The advantage of this is that small indies and creators have a symbiotic relationship that AAA studios and the games press can't compete with. AAA has too much red tape with embargoes and terms which creators hate, while the games press is collapsing under its own weight because they can't risk specializing into a single niche. On the other hand, an indie dev sends a key to a creator and they can have a video on their channel within a couple of hours - everyone wins.

The biggest cost associated with making a game at the grassroots level is your time. The trap I see a lot of developers fall into is over-investing in a concept or a project that didn't get the traction they were hoping for. The sunk cost of a project can easily seduce inexperienced developers into a long development cycle which makes them burn through their limited runway (trust me, I've been there).

There's a certain maturity that is needed to make the tough calls on when a feature needs to be scrapped or even when an entire project needs to get wrapped up early so you can stay alive. Luckily with Gnomes we could feel the spark pretty early on in the play-testing process and our demo launch confirmed it when we were covered by some of the biggest indie creators out there like Splattercat, Olexa and Wanderbots.

Fergus: I guess it speaks to the broader fragmentation of our information landscape that I had to look up all three of those creators.

There is something I’d like to push back on there though, which is this idea that the games press has buckled under its weight. There’s often a prevailing wider narrative that the gaming audience moved from reading reviews on the web to watching videos on their phones and these legacy media brands like Gamespot are just dinosaurs that can’t keep up.

The truth is a little more messy and complicated. Obviously, I’m someone with skin in the game here but I don’t think it takes an insider’s perspective to see that — in addition to the larger headwinds that these outlets have faced in terms of the challenges facing media — many of these brands have also been catastrophically mismanaged by private equity operators looking to pursue incentives that are at best indifferent to the real value the games press can provide to both readers and developers lake and at worst actively destructive to it.

Success in media is rarely as simple, predictable or zero-sum as it can often seem. Of course, to bring things back around to the game development side of things, I have plenty of sympathy with “hyper-indie” developers like yourself looking to circumvent that in favor of working with these smaller creators.

Compared to expensive marketing campaigns that deliver nebulous results, you’re looking at a much more simple and straightforward transaction. Even if that collaboration doesn’t go viral, the overall investment of time and effort from both parties is fairly limited. As you said, it’s all too easy for developers to get over-invested in the thing you’re making and spend less time thinking about what the best way to get it in front of your intended audience is or even what that target market looks like.

Tommy: In 2024, there was something 19000 games released on Steam, and only about 4% of them received 1000 reviews or more. At a glace this can seem quite terrifying, but the reality is, you're not competing with 19000 other games, you’re competing in your specific niche. For example, a PSX style horror game has a much better chance than a puzzle platformer, simply because more players want that type of game and less developers are making them.

When it comes time to marketing your game, you can tell pretty quickly if you've got a feather or a stone. It's hard work no matter what, if your game is meeting a demand that other games aren't, it's light and day. To tie this all together, in my opinion creators have replaced the games press and become the bleeding edge where potential super-fans go to find new games.

You couldn't be more right about the misalignment of incentives in big business. When private equity gets involved, the product of a business becomes their share price or valuation rather than what the company is actually producing. I think in general organizations are suffering from a credibility crisis while the individual creators, experts and thought leaders are asserting themselves as dominant players in those spaces. The dominant organizations out there are now aggregators like YouTube, Amazon and Steam which don't actually produce anything, they facilitate this fragmentation that we're talking about.

To bring it back to games, we see it all the time with publishers and big studios going broke or receiving the wrong kind of attention, while hyper-indies have complete freedom to innovate and tell their stories. You can see the appeal of small games by unknown developers are why they are now regularly considered as Game of the Year candidates without the backing of the press or a marketing team.

Fergus: I mean, everyone loves an underdog story right. At the high-end, games have become a professional industry and the standardisation that comes with that has bred homogenisation not just in terms of tech and visuals but also design.

As corporate as that all sounds, most people would be reluctant to shirk the perks that come with that trend. It’s less interesting that every first-person or third-person shooter relies on pretty much the same control scheme nowadays, but it’s also a lot more convenient and accessible.

I don’t think that dynamic is necessarily new, budgets have swelled and the volume of AAA games in development has shrunk in recent years. I think that’s made these qualities a little harder to overlook than they have been in the past and ultimately helped to heighten the contrast that games made by hyper-indie developers provide.

Production values will get you pretty far but they can sometimes get in the way of the human element of whatever you happen to be sinking your time into. As clunky as it sounds, perhaps the secret to hyper-indie success lies in leveraging not just novelty but humanity.