When did clicker games get so complicated?

How gaming's most straightforward genre evolving

My guest for this week’s issue of Multiplier is Alex Taylor. Alex is the founder of Wristwork, a "artist-led" independent game and interactive media studio based on London.

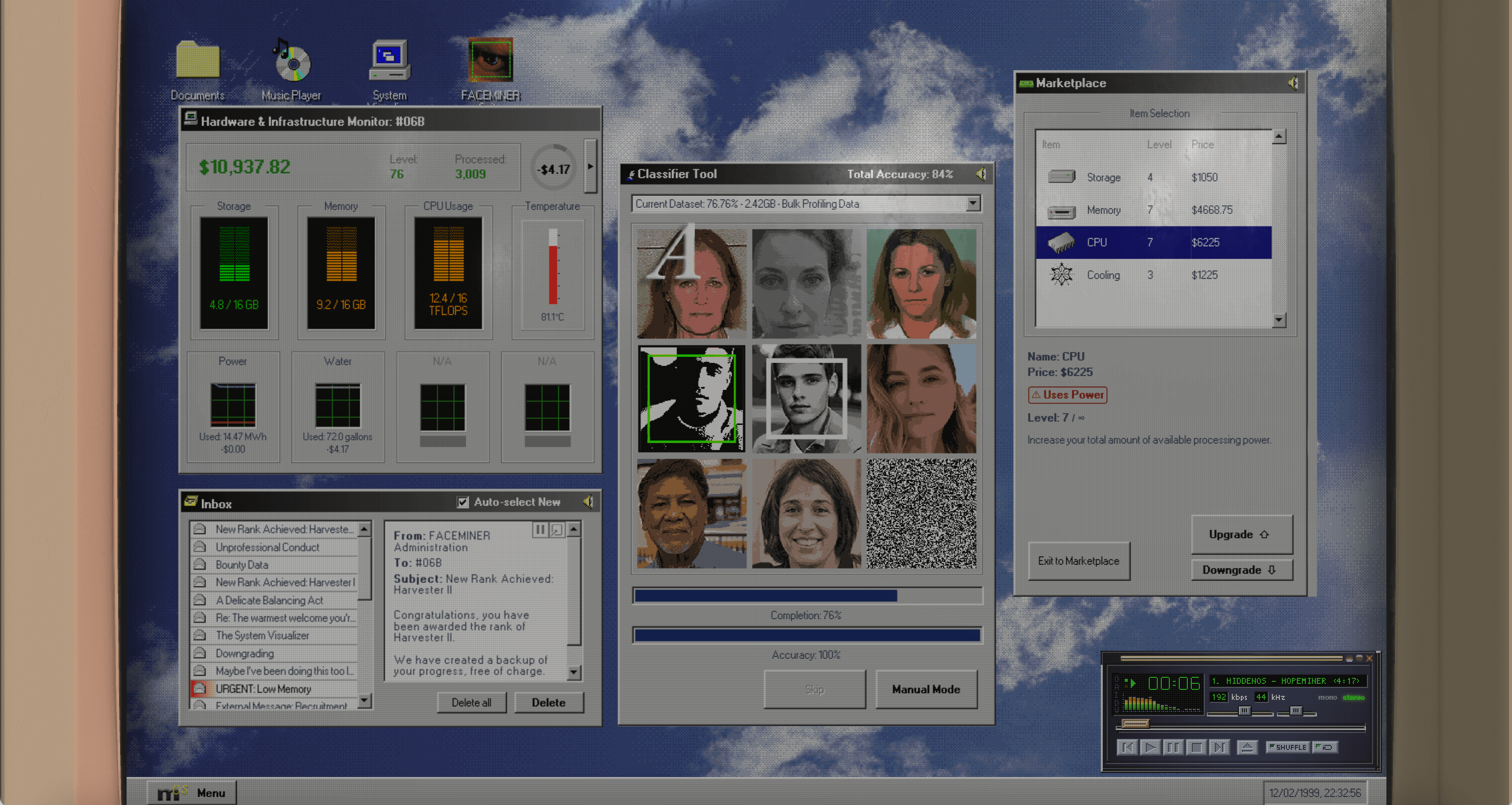

The studio's latest game – Faceminer – was shown at SXSW Sydney earlier this year and I thought it was especially neat so I decided to chase them down for a follow-up chat. You can find Faceminer (which features an original music by Madwreck) over on Steam and follow Wristwork on X and Bluesky.

Fergus: The so-called clicker game has been around for several decades now, but it only feels like we’re starting to see developers complicate the genre by placing it into new contexts. For instance, I recently had a great time with Unfair Flips - which presents you with the challenge of flipping a coin and having it land on heads ten times in a row. That premise sounds pretty mundane but it’s made more interesting by the fact that the odds for a given coin flip begin in a place that’s firmly tilted against you. Eventually, after enough upgrades, you’ll end up with the same 50:50 odds that a real coin has.

Even if the gameplay and presentation involved is fairly bare-bones, I think that Unfair Flips is absolutely successful in its goal of making you question how you think about probabilities. I think there’s a natural parallel between this approach and the one that you’ve taken with Faceminer. The underlying mechanics of the game are driven by clicks but that simplicity is the medium not the message.

Alex: I love the Unfair Flips example, because it does the other thing I love in clicker games, which is when they use these straightforward mechanics as a basis for some pretty visceral worldbuilding. Though I was oblivious to this when I started development on FACEMINER, it does seem we’re in the midst of a clicker renaissance of sorts. I think there's a lot that's appealing about them as a developer - structurally they provide a nice set of constraints to bounce off, and the way they can collapse narrative and mechanics into one means you can play with player agency in some conceptually fun ways. CLICKOLDING feels like another nice recent example of that. Perhaps even more importantly, there’s a large genre-specific fanbase that are both hungry for new experiences and very generous with feedback. If you build it and it clicks, people will come and check it out.

FACEMINER came off the back of some research into cloud data center logistics – I hadn’t originally planned on using it as a basis for a game, but after a while I couldn’t get the Cookie Clicker connection out of my head just due to the recursive self-improving nature of it all. At its core, it's a gamified look at the dangers of any exponentially growing system that feeds off depletable resources without any means for off-ramping. But it’s also a little bit about how our behaviors get programmed by the systems we encounter. So the incremental genre felt like a natural fit for at least two reasons. But I think there's lots of different stories and dynamics these number-go-up mechanics can reveal when placed into different contexts, and Unfair Flips is a nice demonstration of that.

Fergus: I think if I had to pin down another difference between FACEMINER and the other clicker games you’ve mentioned though, it’s likely something to do with the framing and presentation. Your game is far from the first to include a fake computer desktop interface but I do think it’s interesting how that conceit seems to be gaining more prominence nowadays – especially given that entire generations have grown up without necessarily having to navigate it.

This interface isn’t just the main thing that players are clicking through to get the game part of FACEMINER though. It’s also the way in which you’re able to convey a story and create that sense of immersion in the wider world that the game depicts. On some level, the homogeneity of the home operating system market probably makes it such that anything that doesn't look or feel quite like modern Windows or MacOS can feel quite unfamiliar or uncanny. Still, I’m curious. How did you approach that side of things? Was there a specific vision you had from the start or did it evolve over time?

Alex: It’s funny you mention the fake desktop – I have just teamed up with a couple of other developers to create a “retro interface style incremental game” bundle on Steam, so they’re definitely having a moment. At SXSW, where our paths nearly crossed, something that struck me was that when very young kids would try and play FACEMINER, they would try to look around the static 2D desktop as if it had a movable camera (by way of Roblox, I assume). The static desktop with multiple windows seemed to be quite alien, especially when coupled with a mouse. But of course, I grew up with exactly the sort of interface FACEMINER depicts.

Beyond nostalgia, I knew I wanted to set the game within a vintage operating system for a few reasons. The most boring and practical was that as a time-stretched-solo-dev, I was willing to grab any robust set of constraints I could get my hands on. For some of the themes of the game – agency, bureaucracy, boredom – to resonate, it also felt important to remove any separation between ‘player’ and ‘character’. An imagined suite of software, detached from the present day and from any specific place, felt like one path to achieving this.

Setting it in the past was also a convenient way to loosen some of the baggage associated with the very hot topics that the game touches on. I was acutely aware that rooting it in today’s technological landscape would have led to it becoming outdated in 6 months. I mentioned the previous research into cloud data centres – as part of this, I charted the different ways that consumer facing cloud products had been marketed over time since the term’s inception.

As you would expect, the way we talk about these systems has changed a lot since even the late 2000s. By setting the game at the turn of the millennium, it meant I could talk about things more related to the nuts and bolts of bare metal machines – water use, temperature readings, “cluster computing” – in a way that felt authentic enough without it becoming overly technical. With that said, there’s definitely an interesting incremental game to be made within a fake AWS dashboard where you’re wrestling with endless layers of obscure and abstract micro-services.

The late 90s felt like a sweet spot; alien enough to give it the uncanny quality you mention, but clear mappings between where technology was then, and where it is now.