Where is the next generation of gaming nostalgia leading us?

How will tomorrow's game developers reimagine the past?

My guest for this issue of Multiplier is Chad Habel. Habel is a producer at Bad Plan Studios. The Adelaide-based developer is currently hard at work on End of Ember, its debut release. You can follow his work via the Bad Plan Studios accounts on X, BlueSky, Instagram, TikTok and Discord and you can wishlist End of Ember itself over on Steam.

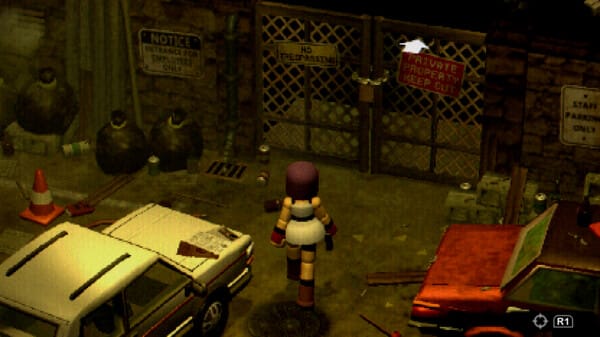

Fergus: The people who make games have always been informed by the games they themselves play. Maybe that's why it's so charming about indie projects that are intended to be a spiritual successor to franchises that have fallen by the wayside, be it a remix of a PC gaming classic like Heroes of Might and Magic or the iconic style of survival horror games associated with the original PlayStation. The line between the likes of Signalis or Crow Country and Silent Hill isn’t just easy to see. It’s easy to appreciate.

Nevertheless, as time marches on, those cultural touchstones and reference points aren't just going to erode. They’re going to be replaced entirely. The next generation of game makers didn't grow up with Final Fantasy. They grew up with Minecraft, Fortnite and Roblox. That’s inevitably going to inform the kinds of gameplay experience they create. The rise of so-called ‘friendslop’ games like Peak and Content Warning are always giving us a taste of what the future of indie gaming might look like in that sense.

Still, given your role as a teacher at Academy of Interactive Entertainment, I have to imagine you’re a little closer to the coal face than I am when it comes to dealing with the kids these days who are looking to break into games. Today's gaming landscape is as obsessed with nostalgia as it is wracked by instability, but what sense do you have of what tomorrow might bring?

Chad: So, I'll start with our studio and say that all three of us founders are unashamedly inspired by Doom. Which Doom? All of them, the idea of it, just Doom. We all loved the original Doom back in the day; Dan has been obsessed with Brutal Doom since it released; and Doom '16 is my favourite video game of all time. So you'll probably pick up the vibe here, and that is that all that is old is new again. We are still seeing a lot of boomer-shooters coming out (312 in pre-release on Steam!) and push-forward design being brought into a wider range of genres and gameplay mechanics. I mean, End of Ember leans pretty heavily on The Binding of Isaac/roguelike tropes, and people seem to get into that.

In general I think that real innovation doesn't connect well with audiences, Bennett Foddy aside. The most successful games (even not counting the 35th reiteration of that sports or shooter game that old mate buys every year) actually lean heavily on their anchors, and are successful precisely because they are pretty familiar to many players.

At most, you'll see a surprising mashup of recognisable genres. So off the top of my head in studios coming up I'm seeing a Crazy Taxi/Simpsons Hit and Run vehicle with a medieval setting; a zero-G racer with a nifty catchup mechanic; a grind simulator with surprising boss fights; a food-themed sci fi RPG with turn-based combat and a cozy/adventure RPG game where you furnish your house to get buffs. Notice how I didn't have to work too hard to describe five very different games? It's because they have firm anchors.

Now when you mention Minecraft, Fortnite and Roblox, I think we may have a paradigm shift towards games-as-platform. This is convergence culture at work: players as creators, consumers as producers: these are UGC-first environments which might mean something very different for the culture. I actually haven't heard of ‘friendslop’ before - that's good though - it's a kind of skibidi-toiletification of game design, maybe? (Trying not to be too boomer-adjacent here.)

On the plus side we might see more incredible work like Split Fiction, for example. Amazing game, but it still knew how to balance anchors and hooks, because it's just not fun to have no idea how to play a game. So I think we'll see a strong line of still quite fun but relatively safe games drawing solidly from tradition, and then some really surprising ones that do turn heads. (And that's not even considering the influence of AI!)

How about you Fergus, what hits your nostalgia buttons? Would you make a game off your own ingrained tastes or go for something much more left field?

Fergus: So I have to just get out ahead of this one and disclose that my partner has done some work on Dungeons & Dining Tables but I do get where you’re coming from in terms of framing things as anchors and hooks, though I can’t help but wonder how blurry the line is between that language being primarily used as a design tool or a marketing one. In either case, I think that there’s a real risk of tunnel vision when it comes to talking about what we do or don’t consider to be an anchor. The games that we might perceive to be without or relying less on anchors may just be leaning on a source that we aren’t familiar with or something that exists a little to the left of the cultural lexicon we’re relying on.

Another thing I want to push back on here is this idea that games like Minecraft, Fortnite and Roblox represent a larger paradigm shift towards treating players as potential creators above all else. There’s more infrastructure around for this stuff nowadays for sure, but the interest in user generated content is hardly new. Whether we’re talking about house-rules for tabletop games, custom Counter-Strike or Warcraft maps, total conversion mods for games like Elder Scrolls and Civilisation or fan-led restoration patches for messy masterpieces like Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodlines or Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic 2, gamers have never shied away from making a game their own.

Perhaps what has shifted over time is the degree to which publishers, developers, and investors are willing to encourage that through formal mod support or discourage it through legal threats. When every other game is locked down by comparison (and arguably by necessity), those who prefer a more sandbox style of play are going to flock to the few titles that err in the other direction. To attempt to wrangle this reply around to your question about nostalgia, I think the approach that most speaks to me is one that looks to take the familiar into unfamiliar territory. Even a failed attempt at adaptation can produce some pretty interesting results, after all.

Chad: Oh yes certainly, the blurred line between design and marketing was intentional. I’m convinced that one of the major reasons for creative or business failure is a deep fracture or imbalance between design and marketing, or creative and technical, or development and business.

Ed Catmull (check out his excellent Creativity Inc.) suggests that a major reason for the success of Pixar is a kind of creative tension between the ‘ugly baby’ and the ‘hungry beast’ - or the creative and business arms of the organisation. And we know that complex systems thrive on not just specialisation but effective connection between those specialised functions: this is key to an ‘ecological’ approach. Deeper collaboration and even some degree of synthesis is necessary for indie studios.

Yes you’re quite right: modding and homebrew have always been a thing, and so maybe recent developments are a difference of degree rather than type. I do think the difference is significant though.

What we are seeing with Epic is that the Unreal Editor for Fortnite is a major content strategy. Epic doesn’t want to run their own development teams anymore… and who would, in this economy? It’s especially challenging at the AAA end of town. Epic wants to provide the tools for creators to do that work for them (maybe buttressed by some nice licensing deals and associated content), and then share revenue with those creators (admittedly, maybe not much of it).

I’m interested in your suggestion of taking the familiar into unfamiliar territory. I’m excited by the potential for a lifetime gamer immersed in, say, Fortnite, to learn some of the basic tools of development and become familiar with Unreal engine via UEFN and then carry that into a fully legitimate gamedev career - what would be a fascinating lived experience [and an example] of the kind of thing we are talking about.

Fergus: Honestly, I’d bet good money that’s already happened. Fortnite has been around for almost a decade now and there absolutely teens who would have grown up with the game and taken that passion to the next level by trying to make a career out of it.

In some ways though, the aspect of this player-to-indie-production pipeline you talk about that most concerns me is the way in which the commercial elements are more front-loaded. For better or worse, the way that Epic frames game development really underlines the degree to which the industry is a business. You might love games, but neither you nor Epic are in this for the sheer love of it.

Much ink has been spilled in recent times on the way in which the concept of ‘selling out’ no longer really holds the cultural sway it used to. These days, it’s all about getting that bread. And when I think about how the next generation might approach game development, I can’t help but worry and wonder where the implicitly commercial nature of their relationship with games (and the tools that they use to make them) might lead us.